GENETIC ETHICS AND NEUROETHICS

Genetics, Neuroethics and Enhancement.

In Thomas Hardy's day, most people thought that "the eternal thing in man, that heeds no call to die" was the immortal soul. In this poem, Hardy distances himself from the conventional wisdom by suggesting an utterly familiar phenomenon as a more plausible candidate.

HEREDITY.

I am the family face;

Flesh perishes, I live on,

Projecting trait and trace

Through time to times anon.

And leaping from place to place

Over oblivion.

The years-heired feature that can

In curve and voice and eye

Despise the human span

Of durance -that is I;

The eternal thing in man,

That heeds no call to die.

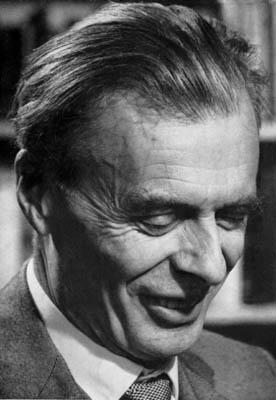

JEMIMA HARDY, THOMAS HARDY'S MOTHER

JEMIMA HARDY, THOMAS HARDY'S MOTHER

THOMAS HARDY.

There is a nice -more personal- take on this in Owen Sheers' poem "Not Yet My Mother":

Yesterday I found a photo

of you at seventeen,

holding a horse and smiling,

not yet my mother.

The tight riding hat hid your hair,

and your legs were still the long shins of a boy's.

You held the horse by the halter,

your hand a fist under its huge jaw.

The blown trees were still in the background

and the sky was grained by the old film stock,

but what caught me was your face,

Which was mine.

And I thought, just for a second, that you were me.

But then I saw the woman's jacket,

nipped at the waist, the ballooned jodhpurs,

and of course the date, scratched in the corner.

All of which told me again,

that this was you at seventeen, holding a horse

and smiling, not yet my mother,

although I was clearly already your child.

From Owen Sheers: The Blue Book.

Copyright (C) Owen Sheers. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge and White Ltd., 20 Powys Mews, London W11 1JN.

The family face is one of many ways by which human race must have been aware of the power of heredity from very early times. But now, testing embryos and fetuses for medical conditions, or testing for the precursors of other physical or psychological characteristics, have given us new ethical questions. Some of the current ones are discussed in Choosing Children: Genes, Disability and Design.

But some of the longer-term questions go deeper. Are there flaws in the human nature that has emerged through Darwinian evolution? Is our darker side (as displayed in war, genocide, torture and other atrocities) deeply programmed into us? Are there limits to our intellectual capacities that may set boundaries to our understanding of the world? These questions raise a debate about "enhancement". Should we attempt to transcend the limitations of the human nature thrown up by the accidents of our evolutionary history? Or are the dangers of any such attempt too huge?

What Sort of People Should There Be? (1984) was a book it was hard to know how to write, as there were no other approaches to draw on or to react against. It was the first book by a philosopher to discuss the ethical issues raised by the power (now actual but then futuristic) to use scientific techniques to choose the birth of people with some genes rather than others. It was also the first philosophical book on what is now called "neuroethics": ethical questions raised by technological interventions in the brain to change (or "enhance") what we are like. The neuroethics part considered the implications of our developing the ability to know about people's thoughts from their brain activity, of the possibility of giving people alternative "virtual realities", and of controlling mental states and behaviour through neurochemical interventions.

What Sort Of People Should There Be?

I say this was "the first book by a philosopher" about these questions, but what is still the greatest book in the field had been published half a century earlier by a novelist. Aldous Huxley's novel Brave New World was also a brilliant and sustained philosophical thought experiment.

What Sort of People Should There Be? tried to explore the arguments on both sides of these genetic and neuroethical issues, and to bring into sharper focus the underlying values at stake. It did not take the then conventional view that any enhancement should be excluded in principle because it would be objectionable "eugenics" or would be "playing God". As a result, it was sometimes seen as a manifesto for enhancement. This was a bit ironic. While the book hoped -then unfashionably- to do justice to the case for enhancement, it was also an expression of a love affair with the unscientific alternative: the everyday ways in which we partly create both ourselves and each other. After looking at what we might lose by rejecting enhancement, it stresses the danger of large scale social experiments (later to be a dominant theme of Humanity, A Moral History of the Twentieth Century). It then mentions another danger:

The danger is that these technologies will be harnessed to a benevolent utopianism which has too crude a view of what life can be. An example is the one-dimensional utilitarianism which aims at the maximum satisfaction of desires. A programme based on this outlook could succeed in harmonizing our desires and the world, at the cost of obliterating the self-expressive and self-creative life we now care about...

One claim here has been that consciousness is especially important: that all value derives from the lives of conscious beings. But it does not follow that pleasurable experience is the only thing of value. A whole life passively consuming pleasure is a narrow one. A broader view of the good life centres on activities and relationships. We mind about the kinds of things we do, and we want to experience things with other people. We also like to think and talk together, sharing and helping to shape each other's responses. In this way we express ourselves, and partly create ourselves and each other. Each of us, to a very small extent, contributes to the development of human consciousness. As a result we, and our descendents, go through life more thoroughly awake.

Some of the ideas of the genetic part of this book were presented in 1983. in a BBC Horizon documentary, Brave New Babies. The documentary, like the book, had to overcome the problem that almost none of the ethical questions were practical issues at that time. The project was to start a debate in time to influence thinking about scientific developments before they became actual. As a result, to some at that time the issues seemed absurdly futuristic and unreal.

The makers of the documentary, David Dugan and Oliver Morse, did a brilliant job of translating the science -and, even more difficult, the philosophy- into television. When the crew came to film at my house, my sons, Daniel and David, aged twelve and nine, successfully argued that they should be on the programme. (My daughter Ruth would no doubt have joined them if she had been a bit older than four.) Daniel and David turned out to be the stars, and their contributions made it a much better programme. I was delighted by their success, though also a little sorry that those who saw it, while rivetted by the children, could not remember anything I had said. Occasionally, in recent years, I have shown the programme to students thinking about these issues. (Now my vanity is piqued in a rather different way. When their elderly, white-haired teacher has finished bumblingly trying to work the DVD player and handed over to them, they then are greatly amused by the glimpse of my younger self before the havoc of more than a quarter of a century of the ageing process.)

SHARING A JOKE WITH JOHN FINNIS.

Soon after the broadcast of Brave New Babies, I took part with John Finnis in a television debate for Channel Four on embryo research. Most of the arguments we used on both sides are now very familiar. The only bit I would wish to preserve is John Finnis's lucid central argument, together with my gently teasing him in my reply to it.

TRANSCENDING HUMAN VALUES?

When people discuss the pros and cons of enhancement, they usually try to weigh up its implications for good or bad in terms of the things we now value. There is an even more radical question. Could our values themselves be in need of modification? Could there be reasons for believing this? If so, how could we recognise those reasons? Is it possible to escape, even to some degree from our own value systems? This is the topic of this paper on Transcending Human Values?