ETHICS AND HUMANITY

Conventional morality is too easy.

“Life is sacred.” “Criminals deserve to go to prison.” “Killing people in war is completely different from murder.” “Never break a promise.” “We should respect the dignity of the human embryo.” “Lying is always wrong.” Each item of these bits of conventional moral wisdom is easy to say. And each is open to serious doubts and objections as soon as questions are asked about its assumptions, and about its human implications. Conventional morality is not only too easy: it is usually too insulated from the imagination and from intellectual curiosity. Intelligent children start to ask questions about this. Who decides what gets on the list of things it is wrong to do? What do the items on the list have in common?

These questions about everyday living are one route into philosophy. But sometimes the big, abstract questions about the world, or about what we can know to be true, are so engrossing that philosophy is not brought to bear on everyday thinking and living.

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN.

You & I were walking along the river towards the railway bridge & we had a heated discussion in which you made a remark about “national character” that shocked me by its primitiveness. I then thought: what is the use of studying philosophy if all that it does for you is to enable you to talk with some plausibility about some abstruse questions of logic, etc., & if it does not improve your thinking about the important questions of everyday life, if it does not make you more conscientious than any … journalist in the use of the dangerous phrases such people use for their own ends. You see, I know that it’s difficult to think well about “certainty”, “probability”, “perception”, etc. But it is, if possible, still more difficult to think, really honestly about your life & other peoples lives.

Some people, often philosophers, have reacted against the haphazardness of conventional moralities by searching for the criterion of right and wrong, some axiom or set of axioms. They may see the solution as obeying the commands of God, or else appeal to a secular criterion such as the Principle of Utility or the Categorical Imperative. Some of these approaches provide, for many widely accepted moral beliefs, a degree of unifying explanation. But, rigidly adopted, the axiomatic approach can create a “Martian” morality through clashing with some of our deepest human responses. We are appalled if obeying God leads Abraham to agree to sacrifice his son Isaac. We are appalled if some secular principle about impartiality leads a parent with only a few places in the lifeboat to say to his or her own children that they must take their turn in the queue.

The hardest questions in ethics are often about finding a middle ground between uncritical acceptance of intuitive responses and abandoning all our emotionally rooted human values in the face of some abstract theory.

Humanity, a Moral History of the Twentieth Century, argued for the importance of the human responses of sympathy and of respect for people’s dignity. The argument appealed to the horrors that can happen when these responses are over-ridden or anaesthetized. But, more generally, there are reasons to think that the purely abstract approach is too detached from other aspects of our humanity, particularly from how our moral outlook is not a purely rationalist affair, but is rooted in experiences and in relationships with people we care about. For instance, values are catching:

RAIMOND GAITA.

The philosopher Plato said that those who love and seek wisdom are clinging in recollection to things they once saw. On many occasions in my life I have had the need to say, and thankfully have been able to say: I know what a good workman is; I know what an honest man is; I know what friendship is; I know because I remember these things in the person of my father, in the person of his friend Hora, and in the example of their friendship… They were not proud in any sense that implies arrogance, and certainly not in any sense that implies they wanted respect for reasons other than their serious attempt to live decently. I have never known anyone who lived so passionately, as did these two friends, the belief that nothing matters so much in life as to live it decently. Nor have I known anyone so resistant and contemptuous, throughout their lives, of the external signs of status and prestige. They recognised this in each other, and it formed the basis of their deep and life-long friendship.

Sometimes people are emotionally drawn to do things that go against the rules laid down, whether by unreflective conventional morality or by some theoretical reconstruction. From the perspective of the rules this is a weakness to be eliminated. But some (not all) of these “weaknesses” are parts of our humanity most of us can understand from the inside. The resulting empathy is also part of our humanity.

ANNA AKHMATOVA.

LOT'S WIFE.

And the just man trailed God's shining agent,

over a black mountain, in his giant track,

while a restless voice kept harrying his woman:

"It's not too late, you can still look back

at the red towers of your native Sodom,

the square where once you sang, the spinning shed,

at the empty windows set in the tall house

where sons and daughters blessed your marriage bed."

A single glance: a sudden dart of pain

stitching her eyes before she made a sound...

Her body flaked into transparent salt,

and her swift legs rooted to the ground.

Who will grieve for this woman? Does she not seem

too insignificant for our concern?

Yet in my heart I never will deny her,

who suffered death because she chose to turn.

Anna Akhmatova.

From Poems of Akhmatova, translated by Max Hayward and Stanley Kunitz. By permission of Darhansoff and Verrill Agency.

HUMANITY IN A DARK TIME.

On September 18, 2001, exactly a week after 9/11, there appeared in the Guardian an article under the heading "Time to talk -a sister of one of the missing calls for conciliation, not retaliation". Excerpts from it:

On Tuesday morning my brother was attending a conference in the World Trade Centre. Since then nobody has heard from him. I keep watching the news coverage in the hope that I will see him on screen. Then I'd be able to ring my other brothers and sisters and say: "He's all right. I've seen him. Everything's going to be OK."

When atrocities have happened to other people and they have reacted with hatred, wanting immediate revenge, I've never condemned them. I've always said that its impossible to know how one would react in such a situation. You can't blame others when you don't know how they feel.

My brother is missing and it's hard to stay optimistic. But I don't want to rush out and attack the people who have done this. I want to understand how it could happen. I want someone to make sure that it never happens again so that other people don't have to experience what our family is going through. Bombing other people will not stop this happening again...

This weekend the government announced that 100 Britons had been confirmed dead and that the figure was expected to rise much higher. I keep thinking about the incredibly small odds that anything could have happened to save my brother, but as the increasingly sensationalist coverage fills our TV screens, and we hear nothing, its hard not to get upset.

How have we managed to get our world into such a mess?

Catherine Dawson.

SOCRATES AND TOLSTOY

The tension in ethics and elsewhere between articulate, questioning rationality and emotional intuition is personified in the contrast between two of my heroes, Socrates and Tolstoy.

Many people in philosophy like labels, and ask about people who teach philosophy whether they are Aristotelian, Kantian, utilitarian, etc. These labels are journalistic and crude. Most of us learn from many of the great philosophers and writers of the past. What a nearly pointless affair philosophy would be if this were not so. And we also develop our own thoughts. I have an extra set of difficulties with such questions. I would want to cite, among others, both Socrates and Tolstoy. But each presents difficulties.

There is no such word as “Socratism”, partly because we know of Socrates’ views almost entirely through Plato and there is the notorious difficulty of disentangling the ideas of Socrates from the contribution of Plato. There is the word “Platonist”, but I do not use it because it is so strongly associated with doctrines about universals, the reality of numbers, etc., which have nothing to do with what I have taken from the doctrines of Socrates as portrayed by Plato. There is the word “Tolstoyan”, but I do not use that because it has been appropriated by groups of dreamy disciples attached to the simple life. And heroes should not be hero-worshipped. It would be hard to see Tolstoy as an ideal husband. And I disagree with most of Tolstoy’s major official doctrines, about religion, about the wisdom of the peasants, about art and about absolute pacifism.

So here I will just signal some of the things I have admired and tried to borrow from Socrates and Tolstoy, and indicate a certain tension between them.

Neither you nor I nor anyone would prefer doing wrong to suffering wrong, since the former turns out to be the greater evil

Taken literally, this thought ascribed to Socrates is obviously false. Bankers, whose greed contributes to wrecking the economy and to other people losing their jobs or their houses, choose to retire on huge self-awarded “bonuses” rather than change financial places with their victims. Not everyone prefers suffering wrong to doing wrong.

But the deeper point is the claim that (whether or not murderers, torturers, corrupt politicians, cheats, and the rest of us see this) doing wrong is worse for a person than suffering wrong. Since I first read Plato at school, this thought has been nagging somewhere at the back of my mind without my ever quite coming to terms with it. As a universal generalization, it too seems obviously false. In the course of making off with a huge fortune, a robber causes severe permanent brain damage to a security guard. The robber is never caught and lives a comfortable life on the proceeds. It is wildly implausible to say the security guard is better off than the robber.

But, lurking underneath the obvious falsehood, there seems to be a hard-to-formulate deep truth. It is almost certainly not a universal generalization, but for many of us serious evil-doing often has huge psychological costs. (Here Socrates and Dostoyevsky seem to inhabit the same territory.) Even if not all murderers are as psychologically burdened afterwards as Raskolnikov, many may still find it harder to be at peace with themselves. There are strong human dispositions to cruelty, ruthless selfishness and so on. But there are countervailing dispositions towards kindness and towards respecting people, and a deep reluctance to torture or kill. There is also a countervailing concern with the sort of person one is or wants to be.

Because our psychology is complicated and conflicting in these ways, terrible acts often do make it hard to be at peace with yourself. Socrates gives this as part of his case for being moral even when doing so has, in external worldly terms, more costs than benefits.

There can be no greater good for a man than everyday to discuss goodness and all the other things you hear me examine myself and others about, for the unexamined life is not worth living.

Visiting the Acropolis, Vivette and I noticed a sign "To the Prison of Socrates". I don't know how good the evidence is for this being where Socrates drank the hemlock while he carried on arguing about the obligation to obey the law. (Though it is well supported that this "prison" was where treasures from the National Museum were hidden for safety -with the entrances concreted over- during the Nazi occupation.) But the claim that it was the prison of Socrates made a visit irresistible.

Another thing that, like thousands of others, I have admired and tried to borrow from Socrates is his demand that we try to be clear and articulate in the questioning and examination of ourselves, our beliefs and our values. If we leave all this in a vague, unexamined blur, we are likely to be slaves of local prejudices or of our upbringing in how we think and act. The Socratic demand for the explicit and precise statement of beliefs and values, and the further demand to expose them to the challenge of counter-arguments, is not just uncomfortable but also liberating. And, also important, all this makes it less likely that we will, as John Donne said, go through life never thoroughly awake.

Tolstoy on the whole prefers people who trust their intuitions and who may be, like both Pierre and Levin, fairly inarticulate in discussion. He is suspicious of theorizing as glib and shallow. Napoleon is defeated by Kutuzov’s deep feel for what is likely to happen to a foreign army in Russia, rather than by younger and intellectually sharper soldier-strategists. Levin finds that economic or other abstract theories about the reform of agriculture fail because they have no room for any intuitive feel for how reforms will be defeated by the pig-headed stubbornness of the Russian peasants. And when he does discuss disagreements, it is not argument that may persuade, but the sudden breakthrough of an intuitive feel for the other person’s vision.

Levin had often noticed in discussions between the most intelligent people that after enormous efforts and endless logical subtleties and talk, the disputants finally became aware that what they had been at such pains to prove to one another had long ago, from the beginning of the argument, been known to both, but that they liked different things, and would not define what they liked for fear of it being attacked. He had often had the experience of suddenly in the middle of a discussion grasping what it was the other liked and at once liking it too, and immediately he found himself agreeing, and then all the arguments fell away useless. Sometimes the reverse happened: he at last expressed what he liked himself, which he had been arguing to defend and, chancing to express it well and genuinely, had found the person he was disputing with suddenly agree.

When Vivette and I were students first getting to know each other, she felt that there were human things I needed to know. Her way of encouraging me to learn about some of them was to give me a copy of Anna Karenina. Reading it was one of the changing and enriching experiences of my life. For many years I have encouraged students who have not read it to do so.

LEV TOLSTOY.

Many years later, Martha Nussbaum invited me to talk about a novel to her seminar on philosophy and literature at Brown University. I explained that I did not, and would not be able to, write or give a talk about novels. Martha replied by asking me what was my favourite novel. I said it was Anna Karenina. "All right. I will put you down for "Anna Karenina and Moral Philosophy". The article below grew out of the talk I gave. It appears in a Festschrift for Jim Griffin: Wellbeing and Morality, Essays in Honour of James Griffin, edited by Roger Crisp and Brad Hooker. I should have liked to have contributed an article about Jim's own work, which I admire. But it was a time when I was under a lot of pressure and knew I would not get it done in time. But as Jim knows well so many of the human things Vivette hoped I would come to know, I hoped this paper might be a suitable tribute.

Here is my attempt to express some of the things I started to learn when Vivette first gave me the book:

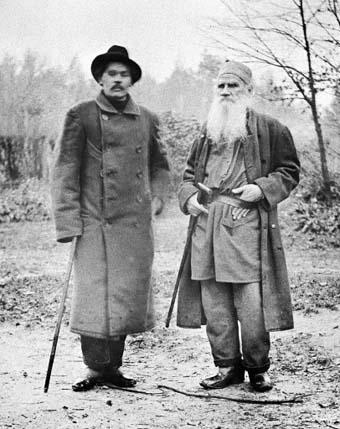

TOLSTOY WITH CHILDREN.

For a number of years visits to Moscow have been enlivened by a scientific colleague of Vivette's and a friend of both of us, Alexei Medvedev. He has taken us on many visits, including one to Chekhov's house. The most interesting of all was to Tolstoy's house at Yasnaya Polyana. Because of the influence Tolstoy has had on Vivette and me, this visit was one of the most memorable days in our life.

THE WOODS AT YASNAYA POLYANA.

It was at Yasnaya Polyana that I saw him again. It was an overcast, autumn day with a drizzle of rain, and he put on a heavy overcoat and high leather boots and took me for a walk in the birch wood. He jumped the ditches and pools like a boy, shook the raindrops off the branches, and gave me a superb account of how Fet had explained Schopenhauer to him in this wood. He stroked the damp, satin trunks of the birches lovingly with his hand and said: “Lately I read a poem: The mushrooms are gone but in the hollows Is the heavy smell of mushroom dampness… Very good, very true.”

Suddenly a hare got up under our feet. Leo Nikolaevich started up excited, his face lit up, and he whooped like a real old sportsman. Then, looking at me with a curious little smile, he broke into a sensible, human laugh.

GORKY IN THE WOODS WITH TOLSTOY.

Our values are not completely insulated from episodes like the hare leaping up. Richard Keshen, commenting on an e-mail of mine about seeing two foxes behind my house in the snow, wrote, “I know what Jonathan means by the “alien beauty” of foxes. Mary and I were out walking a few years ago and a fox appeared on our path. We looked at the fox and the fox looked at us for what seemed a long time, but was probably no more than 15 seconds. Having taken its fill of us, it turned and disappeared. After my mind refocused, I had quasi-Kantian thoughts about animals –as I often do-: they have lives as singular as our own; that they should be left to lead their lives; that their moral status rests on something deeper than the satisfaction of their interests and the avoidance of pain –the kind of intuition, I think, that pulls against the two tier view that Jeff [McMahan] so eloquently defends, or the one-tier view that Peter [Singer] makes the basis of his ethics.”

Tolstoy's grave at Yasnaya Polyana, where his brother Nikolai told him the green stick was buried.

I used to believe that there was a green stick on which words were carved that would destroy all the evil in the hearts of men and bring them everything good, and I still believe today that there is such a truth, that it will be revealed to men, and will fulfil its promise. Since my body has to be buried somewhere, I have asked that it be in that place, in memory of Nikolai.

I want to be on the side both of Socrates and of Tolstoy. An attempt at this enterprise (possibly a doomed one, though I hope it is not) was my inaugural lecture at King’s College London.

LINK TO “SOCRATES, TOLSTOY AND MEDICAL ETHICS”, INAUGURAL LECTURE, KING’S COLLEGE LONDON.

ADVERTISEMENT FOR MYSELF? -BUT MAINLY FOR SOME DISTINGUISHED CRITICS AND COMMENTATORS.

The title of this section of the website has been borrowed from a book edited by my friends Ann Davis, Richard Keshen and Jeff McMahan: Ethics and Humanity, Themes from the Philosophy of Jonathan Glover. These questions about the human and emotional strands of morality and how they interact with the rational and critical strands are a central theme of the book. As well as articles by each of the three editors, it includes articles by Allen Buchanan, Roger Crisp, James Griffin, John Harris, Thomas Hurka, Martha Nussbaum, Onora O’Neill and Peter Singer, together with my responses to the articles.

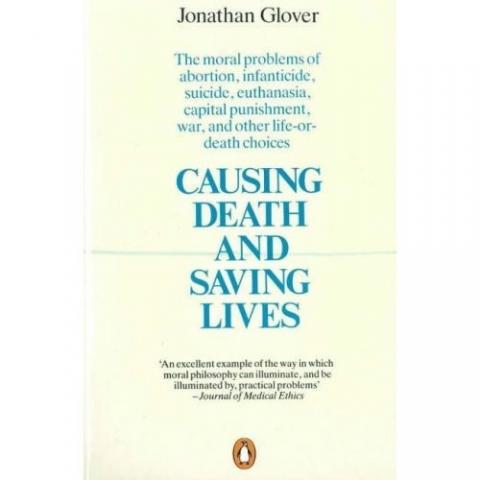

ETHICS OF LIFE AND DEATH

Causing Death and Saving Lives started with the words “Many of us find moral problems about killing difficult, and most of those who do not should do”. The book was written partly because my own thinking about particular issues (abortion, euthanasia, capital punishment and war) had been shaped by responses to each particular issue. But I knew the reasons for taking a view on one of these issues had implications for the others, which I had not worked out. There were discontinuities in my thinking, which were difficult to sort out. And these discontinuities were also there in the thinking of other people, who often did not see any difficulty in them: “most of those who do not should do”.

There was also a need to work out a general account of why killing was wrong, to replace the “sanctity of life” account. To a religious believer, that account –“killing people is wrong because life is sacred”- might imply that the sanctity comes from God, which would give a reason of a kind for not killing. But, for non-believers, can “life is sacred” explain, rather than merely repeat, the claim that killing people is wrong? And, if the reason for not killing people is the wrongness of taking life, it should be just as wrong to kill a mosquito. More needs to be said about the special wrongness of killing people.

The slack thinking that leaves people untroubled by the discontinuities contributes to much unnecessary death and misery. There are too many people appalled by abortion, but who support capital punishment, or who far too easily support a war. In the American election of 2004, many who voted to re-elect President Bush cited “moral values” as determining their vote. They often had Bush’s opposition to abortion in mind. I wonder how many of them had opposed the Iraq war on the basis of these “moral values”. Nietzsche once spoke of someone’s outlook as being his own “antipodes”. The “pro-lifer” who easily supports war and capital punishment is, in this area, my antipodes. Causing Death and Saving Lives aimed to make such complacency a bit harder to sustain. Its central core is that we should look for a coherent approach to our life and death decisions, in which consequences for people’s lives and respect for their autonomy should come before abstractions about the sanctity of life, retribution, the dignity of the embryo, the national interest and so on.

This general approach has been taken up and developed in different directions by a number of philosophers. My version of it gave a central approach to both people’s interests and to respecting their autonomy. Peter Singer then developed a version that was based purely on interests without special reference to autonomy, but extending its scope to include non-human animals. John Harris developed a version with a strong emphasis on a blend of liberty and equality. Other variants have been developed. Perhaps the most sophisticated is the one developed in two volumes (The Ethics of Killing: Problems at the Margins of Life and Killing in War) by Jeff McMahan. What all these versions have in common is a rejection of any idea of the sacred, together with a shared project of basing respect for life in broader human values.

Public debate about life and death issues is often, unsurprisingly, passionate. People rightly care about these questions. But, when not rooted in thought about the underlying philosophical issues, the debates also have an angry dogmatism partly coming from intellectual insecurity. The abortion issue is striking in this respect. People passionately take sides (“pro-life” or “pro-choice” in the simplifying labels) and they so much want the issues to be simple. Hard edges, not complex gradations. So the official doctrine of some pro-life people is that the newly fertilized egg is as much a person as you and me, and taking the morning-after pill is literally murder. And the official doctrine of some pro-choice people is that abortion is morally like removing an appendix: the only moral issue being about the woman’s control of her body.

Neither of these official doctrines is remotely plausible. People are only led to believe these claims because they are taken to be essential parts of some simplifying moral package deal needed for the pro-life or pro-choice position. And probably people claiming to accept the doctrines do not fully believe them. Having to choose between saving one four year old child and ten fertilized eggs in a Petri dish, the pro-life theorist would probably do the same decent thing the rest of us would do. And a woman considering having an abortion is most unlikely to think the choice as unproblematic as one about removing an appendix. Some minimal awareness of insecurity about these official doctrines probably contributes both to the hostility shown to more complex views and to the anger and heat of the debate.

RIVAL DEMONSTRATORS.

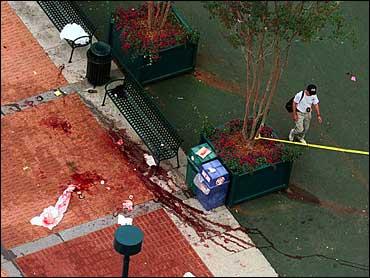

THE BOMBING OF AN ABORTION CLINIC IN ATLANTA.

I once tried to contribute to reducing the heat and anger of the debate about abortion, and to show both sides that they had more in common about an issue more complex than they liked to think, in an article in the New York Review of Books. It was published in the mid-1980s and made reference to the then current American politics of abortion. But it is relevant today as the underlying structure of the debate is unchanged.

Matters of Life and Death, New York Review of Books

Unsurprisingly, my peacemaking attempt was criticised from both sides, although I was pleased that in the end my critics on both sides and I had friendly personal exchanges.

The Morality of Abortion - An Exchange

Causing Death and Saving Lives argued that some newborn babies have such poor prospects of having a life which, from their own point of view, would be worth living, that it is not a kindness to keep them alive. Of course judgements about when this point has been reached are very difficult, but where parents and the medical team are agreed on this, the baby should be allowed to die. And where “allowing to die” is either ineffective or cruelly slow, it may be right to take positive steps to end the baby’s life. This view greatly divided readers. Some thought it was right, even obviously right. Others were appalled by it. Many who had strong views one way or the other had little direct experience of the issue. (Although some on both sides who wrote to me did have direct experience. My own views came partly from close experience and partly from philosophical thought about the values involved.) I have always been struck by the way the very confident views mainly come from those remote from experience of the dilemmas, and how family members or medical teams confronting the problems are a good deal less certain about things.

There was a reminder of this when, several years ago I revisited these issues in a lecture at Great Ormond Street Hospital. The audience included some family members, some legal people involved, and many medical people whose professional lives were bound up with these problems. The topic was what should be done when the family and the medical team disagree about whether the child should be kept alive. In the discussion, that audience had an openness and a quiet seriousness unlike any other.

Should the child live? Doctors, families and conflict

My early book was not just about causing death, but also about saving lives. And on that too my views needed updating. I tried to do the updating in this talk at a conference at the London School of Economics, run by the Forum for European Philosophy, on philosophy and world poverty.